On December 28. 2019, Joan Hollobon was awarded the Order of Canada. Due to COVID-19, the investiture was delayed and took place on March 29, 2021, at Kensington Gardens, the long-term care home where Joan lives .

By Andy F. Visser-de Vries

Joan Hollobon’s life and daily routine as a resident at the Kensington Gardens long-term care home is rather quiet and inauspicious. She likes to sit in her wheelchair by the nursing station on the fourth floor during the day to interact with the staff and she still reads The Week, an international news magazine that provides her with a summary of recent world news and events.

While she is hard of hearing and she can’t be bothered with ‘those damn hearing aids’, she loves to welcome visitors and reminisce about family and friends. The walls in her private room are covered in a rich tapestry of photos that tell her life story – photos of her parents, her grandmother, and her aunt May, and others from Joan’s career and with her friends. And then there are the photos of Achilles and Ching and Misty, her cherished German shepherd dog and her two Siamese cats that died long ago but still brighten Joan’s expression whenever she looks at them.

Joan picking up her mail at Kensington Gardens, where she lives.

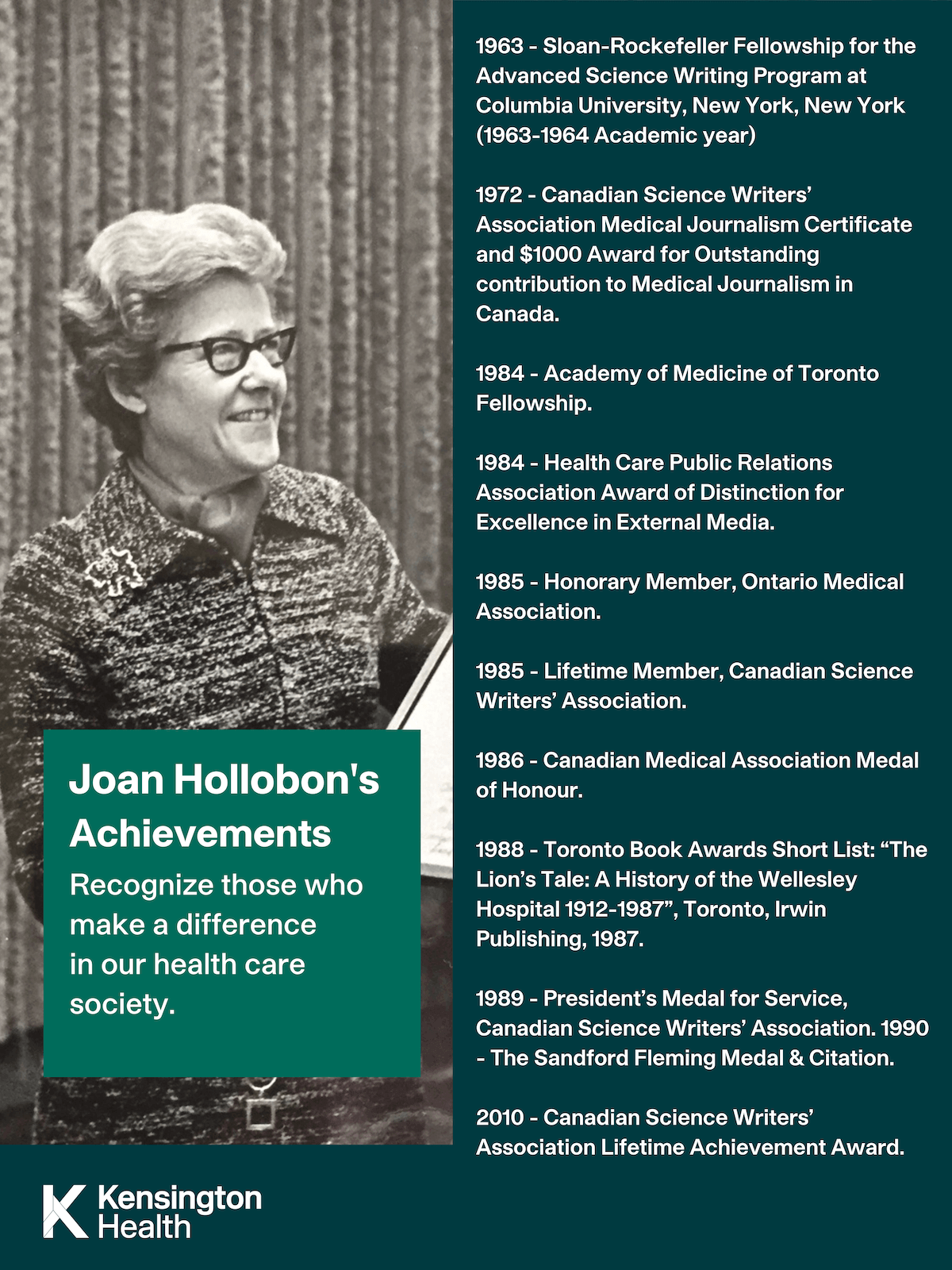

Joan May Hollobon, who celebrated her 101st birthday on 29 January 2021, is a friend, a mentor, and a former medical reporter for The Globe and Mail. I was proud to nominate for the Order of Canada for her outstanding contribution to the Canadian public. In her role as medical reporter for The Globe and Mail from 1959 until her retirement in 1985, Joan Hollobon served as a pioneer in the print media to help bridge the large gap in understanding and awareness that existed between the medical profession and the general public.

Joan and Andy, her friend and caregiver, in Vancouver 1997

Her career that spanned the founding of medicare in Canada to the early days of the AIDS pandemic, and her hands-on reporting helped to foster and establish a dynamic relationship between the medical profession and the general public that we take for granted today. Joan Hollobon helped to change not only the way patients and the general public approach their doctors and interact with them, but also the way doctors approach their patients and the general.

When Joan Hollobon was first appointed the medical reporter for The Globe and Mail in August 1959 (on an interim basis), illustrative of the time 60 years ago, editors at The Globe were less than enthusiastic about having a woman on the medical beat. But The Globe needed to replace David Spurgeon, the medical reporter at the time who had been awarded a one-year study fellowship at Columbia University in New York. Joan Hollobon had proved herself a reliable general reporter since starting at the paper in October 1956, and so she was asked to fill in as the medical reporter for the coming year.

Armed with her newly purchased concise medical dictionary and a steely resolve, Joan was determined to learn her craft well, if only for the one-year assignment. But when David Spurgeon returned from New York in July 1960, he was assigned to the newly-created science beat, and Joan Hollobon became the permanent medical reporter, a position she held for the next 26 years until her retirement in January 1985. The move to medical reporting proved auspicious, not only for Joan Hollobon, but also for the Canadian medical profession, patients, and the general public.

Looking back now, it is difficult to appreciate the overwhelming barriers women faced in the workplace in general, much less what Joan faced as the first female medical reporter for a national Canadian daily newspaper. But through grit and determination, she gained the respect of her colleagues, her editors-in-chief, the medical profession, scientists, and the general public.

What made Joan Hollobon unique as a reporter, and a medical reporter per se, was that while she had an office desk at The Globe, she was always in the field learning hands-on. In this age of the Internet where many people research medical diagnosis and potential cures to equip themselves in discussions with their doctors, it is difficult to appreciate the role Joan Hollobon played when it came to equipping the general public with an understanding of the medical profession and their own personal health care.

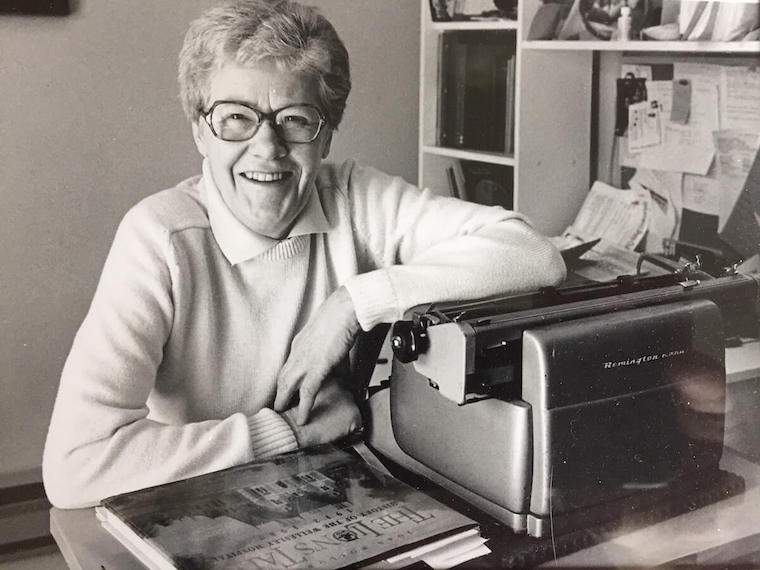

Joan accepts a writing award in 1973

Joan opened the door for patient health advocacy through increased awareness, open dialogue, and a medical profession that changed the way it talked down to people into an approach that involved talking with people.

Joan Hollobon had learned her craft well.

Over the years, Joan Hollobon touched on almost every area of clinical medicine, medical research, and medical politics in her writing. In July 1962, she travelled to Saskatchewan to witness the difficult birth of medicare – something Canadians take for granted today. Commonly referred to as the 1962 Saskatchewan Medicare Crisis, doctors went on strike against the founding of universal medicare in that province for 23 days.

Joan Hollobon was there to report first-hand. Her reports appeared in The Globe daily during the 23-day strike, and as a result she helped to educate the Canadian public about the merits of universal health care. Joan was well-placed to cover the Saskatchewan Medicare Crisis because universal medical insurance was something she learned about first hand in England. Her mother died of bone cancer in 1948 two years after the UK government introduced the National Health Service Act which completely changed the way people could access healthcare.

Joan continued to follow the progress of events in Saskatchewan closely after the dispute was settled and wrote a 10-part series on the state of affairs in that province for The Globe and Mail entitled, “Bungle, Truce and Trouble”. Her writings were later published as a small booklet distributed for free by The Globe.

Years later, Joan Hollobon reflected on those three weeks she spent in Saskatchewan in the early summer of 1962. “Research to me was the most interesting, but medical economics and politics were also part of the medical beat. (It was) another totally different experience – the three weeks of the Saskatchewan Medicare Strike beginning on 1 July 1962, working almost around the clock, 7 days a week. The rhetoric and the passions aroused! So un-Canadian. Everyone was slightly around the bend by the end of it. Everyone thought then that Saskatchewan, 1962, was an experience no political or medical group would ever risk repeating. So much for that theory.”

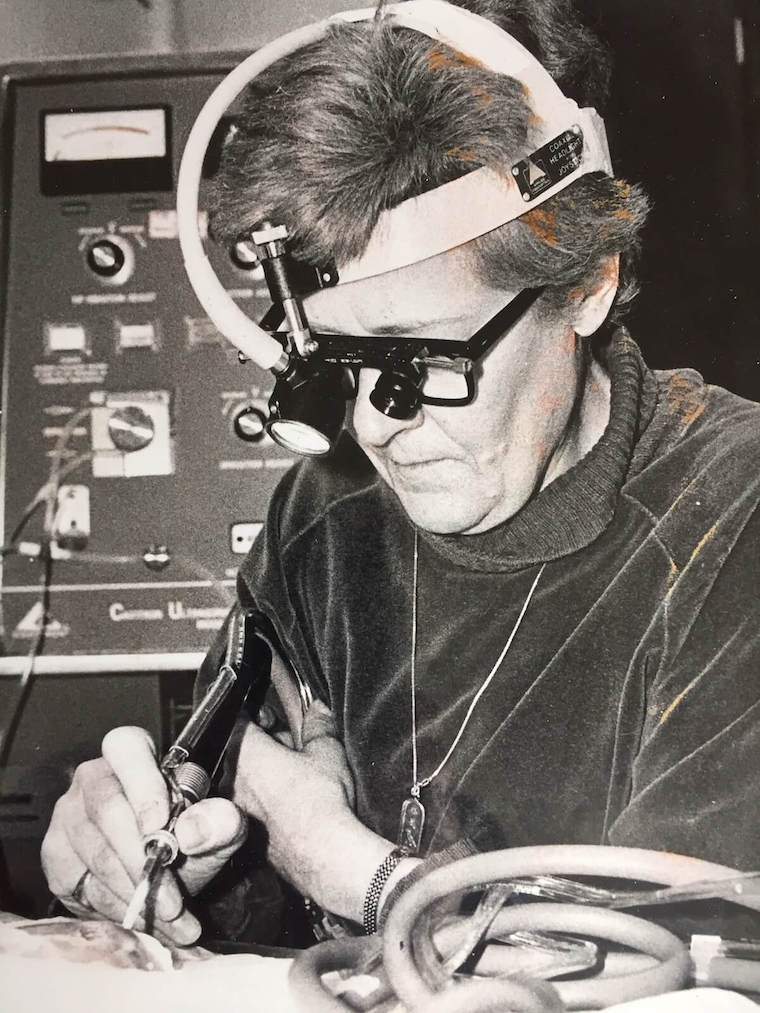

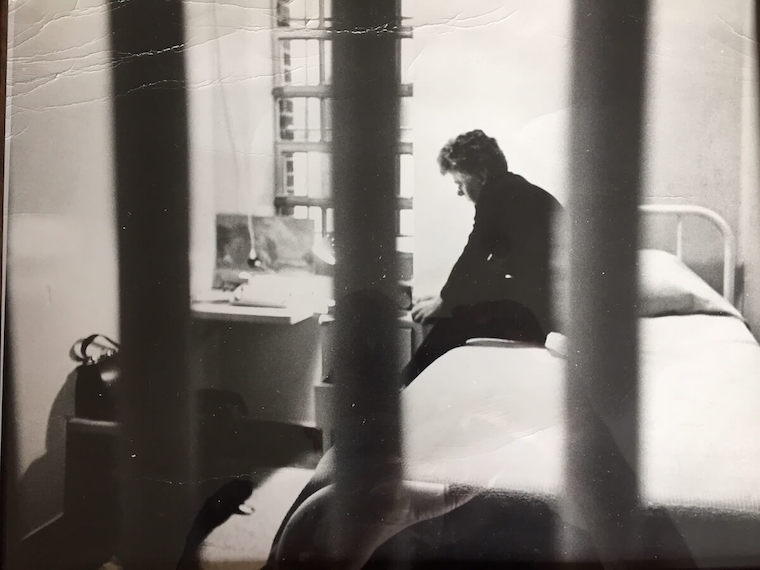

Joan at Penetanguishene institute for the criminally insane 1967

In March 1967, Joan Hollobon checked herself in at the Oakridge maximum security division of the Penetanguishene Mental Health Centre (formerly known as the Hospital for the Criminally Insane) in Penetanguishene, Ontario, where she worked and slept from a cell among the 38 inmates for four days. Joan Hollobon’s article, “Behind the Bars on G Ward” appeared in The Globe and Mail’s April 1968 weekend magazine supplement to the daily newspaper. It unlocked the doors to a world few Canadians were aware of, and explored a completely new and different side of healthcare that would have startled many people. Later, reflecting on her career as the medical reporter for The Globe and Mail, Joan stated, “The assignment that left the most lasting impression was the 4 days I spent locked in the Oakridge Maximum Security Division of the Penetanguishene Mental Health Centre with those 38 patients. Perhaps it was unforgettable because it provided insight into people whose life experiences and lifestyle most of us rarely encounter, or because of the insight into oneself through encounters in an intense programme that stripped away the usual social superficialities.”

Perhaps that was the key to Joan Hollobon’s success as a medical reporter – not only was she able to capture the attention of her readers by her thorough hands-on medical research and reporting, but she was empathetic when it came to dealing with and recognising the human condition.

In 1972, Joan Hollobon wrote a series of three articles on transsexuality and the first sex reassignment operation performed in Canada published in The Globe and Mail on 31 March, 1 and 3 April 1972. The ground-breaking series won Joan Hollobon the 1972 Canadian Science Writers’ Association (CSWA) Medical Journalism Certificate and $1000 Award for Outstanding contribution to Medical Journalism in Canada, presented to Joan by Ortho Pharmaceutical (Canada) Ltd. in 1973 at the annual conference of the Canadian Science Writers’ Association.

Joan, 1964, in one of her favourite cars

After interviewing thousands of people and covering an equal number of subjects and miles travelled during her career, Joan Hollobon worked her last day as the medical reporter at The Globe and Mail on 31 January 1985, and took her retirement on 1 February 1985, aged 65 years old.

Joan Hollobon not only helped to change the way patients approached their doctors, and how doctors approached their patients, or how Canadians understood healthcare, but she was a mentor and respected by her peers, the general public, and the medical profession.

One morning in the late 1970s, Joan Hollobon was called into the office of the Editor in Chief of The Globe and Mail. He handed Joan an envelope that had been sent by a lawyer and inside the envelope was a cheque for $1000 with a letter stating that an anonymous donor wished to give the money to Joan Hollobon in recognition of her skill as a medical reporter and with the hope that Joan would use the money to attend a writer’s conference of Joan’s choice as part of her professional development. And Joan accepted. But Joan Hollobon went a step further. For the next 25 years, Joan would quietly write a cheque for $1000 annually and send it to a different woman in the field of journalism to be spent on professional development.

Joan Hollobon’s career as the medical reporter for The Globe and Mail afforded her some unique experiences outside the medical field. In May 1960 Joan Hollobon flew on special assignment for The Globe and Mail in a Sabena Airlines Boeing 707 on its’ inaugural flight from Montreal to Brussels. She then travelled to England where she covered the wedding and honeymoon departure of Princess Margaret and Mr Anthony Armstrong-Jones for The Globe and Mail.

When Joan Hollobon received the Canadian Medical Association Medal of Honour in 1986 for bridging the gap between the medical profession and the general public through her hands- on reporting, she reflected on her retirement and her long career as a medical reporter with these words:

“There is surely no greater good fortune than to be able to earn one’s living doing a fun job that offers unlimited opportunity to learn new things. It seems fainting immoral to receive an award for such good fortune, which included the luck to work for a newspaper that cared about trying to get things right. I decided I could accept it (the Canadian Medical Association Medal of Honour) gratefully on two counts. First, as a recognition by the medical profession that talking to the public is worth doing. When I began medical reporting for The Globe and Mail in 1959 that view was less prevalent. And second, as an honour to be shared with journalist predecessors and colleagues still out there doing a conscientious job. While reporting might have seemed awfully trivial, for medicine at its’ best is still considered among the noblest of callings, the best has never been so subject to differing interpretations, and the ordinary patients, the same old human bag of bones lying in a bed, hurting and scared – may have more old-fashioned virtues in mind.

And, of course, taxpayers are entitled to know what is being done with their dollars. The paucity of support for research can be directly linked to ignorance of what is being done or the need for it.

If communication can help bridge the widening gaps in all these area between an increasingly impersonal medicine and the people in the street, then it is worth doing.

So, I’ve had an awfully good time learning about medicine from a lot of terrific people - the many people who I have interviewed, argued with, written about and learned to respect. Thank you – and please go on talking to all those other science writers out there!”